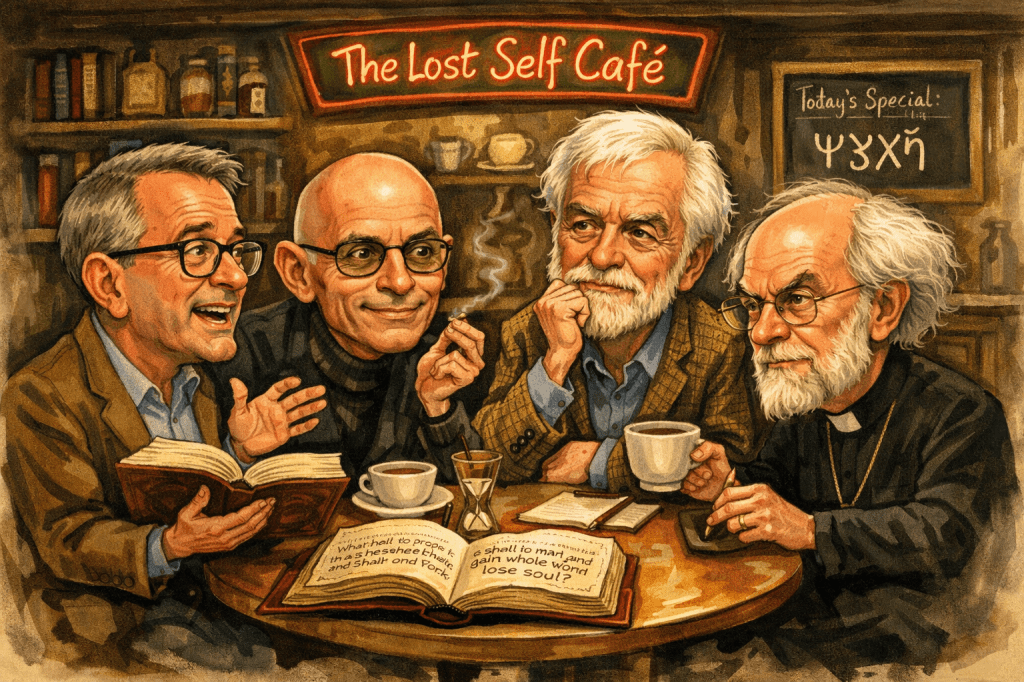

Inspired by the Higher Self Café

Have Tom Stoppard write Joel B. Green, Michel Foucault, Charles Taylor, and Rowan Williams as they exegete Matthew 16:25, and trace the historical/theological progression of losing “life” instead of “soul.”

ChatGPT Prompt

A café that seems to have misplaced itself.

The menu lists drinks like:

- Ego Macchiato

- Buffered Latte

- Anima Americano

A chalkboard reads:

Today’s Special: ψυχή (psychē) — ask your server what it means

Act I — The Verse on the Table

GREEN (reading from a battered King James Version):

“For whosoever will save his life shall lose it: and whosoever will lose his life for my sake shall find it.”

— Matthew 16:25, KJV

(Pause.)

GREEN

It’s the same Greek word. Twice. ψυχή (psychē).

And they translate it twice… differently.

FOUCAULT (sipping)

Ah. The text has already begun to confess.

TAYLOR

Or to protect itself.

WILLIAMS (gently)

Or to protect us from it.

Act II — The Lexical Crime

Green States the Problem

GREEN

No first-century Jew would hear “biology” here.

Psychē names the self as a living, desiring whole within

Second Temple Judaism.

Translate it as “life” and you turn existential surgery into… heroics.

FOUCAULT

Heroics are governable.

GREEN

It isn’t martyrdom rhetoric.

You can’t “gain the whole world” while dead.

FOUCAULT

True.

But you can govern a population very well if they think salvation is postponed until after death.

(Beat.)

GREEN

That is not a footnote.

Act III — How the Soul Became a Liability

Foucault Rewrites the Plot

FOUCAULT

Originally, spirituality meant losing oneself —

askēsis, danger, unmaking.

Then Christianity became useful.

So the soul was preserved, inspected, audited.

- You don’t lose it.

- You manage it.

TAYLOR

Which requires that the self remain intact.

FOUCAULT

Precisely.

A soul that can be lost is a soul that cannot be administered.

GREEN

So the interpretation shifted—

FOUCAULT

—and the word became embarrassing.

Act IV — The Buffered Self

Taylor Explains the Modern Condition

TAYLOR

By the modern period, the self is buffered — sealed, protected, autonomous.

Any command that threatens dissolution sounds pathological.

- “Lose your soul” sounds abusive.

- “Lose your life” sounds noble.

So translators do not ask, What did this mean?

They ask, What can a modern self survive hearing?

See:

- Charles Taylor, A Secular Age

- “The Buffered Self”

FOUCAULT

A pastoral concern masquerading as philology.

GREEN

Or cowardice masquerading as clarity.

Act V — Williams Ruins Everyone’s Comfort

Williams Speaks Softly

WILLIAMS

What if the terror is justified?

(Silence.)

The self Christ addresses is not meant to survive intact.

The Church learned to say “Christ saves you”

when Christ was actually saying “Come and be undone.”

We kept the creed.

We lost the wound.

See:

- Rowan Williams, The Wound of Knowledge

- Kenosis (cf. Philippians 2:7)

TAYLOR

So the translation changed because the practice disappeared.

WILLIAMS

Yes.

Words survive practices only briefly.

Act VI — The KJV Confesses

(The KJV on the table flips open by itself.)

“What shall it profit a man, if he shall gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?”

— Matthew 16:26, KJV

GREEN

They couldn’t eliminate it entirely.

FOUCAULT

No.

Every regime leaves behind a relic it doesn’t know how to use.

TAYLOR

Or a question it cannot answer.

WILLIAMS

Or a Christ it cannot quite follow.

Closing — The Bill Arrives

(The server brings the check. It reads:)

To be paid in full: your self

FOUCAULT (smiling)

Ah. The original economy returns.

GREEN

So Christianity didn’t lose the word.

TAYLOR

It lost the courage.

WILLIAMS (standing)

Or perhaps it misplaced it —

waiting for someone foolish enough to mean it again.

(Lights dim. The chalkboard now reads:)

Tomorrow’s Special: “Whoever has ears — ask what they cost.”

— cf. Matthew 11:15

Epilogue

The tragedy is not that Jesus said “lose your soul.”

The tragedy is that we learned to read it without trembling.

And then — very carefully —

we translated the trembling away.

Appendix I: The Thinkers

A concise guide to the four interlocutors at the Lost Self Café—why each matters, and what they uniquely contribute to recovering Christ’s “soul.”

A. Joel B. Green — ψυχή as the Whole Self

Joel B. Green is a New Testament scholar whose work decisively reframes ψυχή (psychē) in the Gospels as relational selfhood, not a detachable metaphysical entity and not mere biological life.

Green shows that within Second Temple Judaism, psychē names the whole living self—the center of desire, agency, and orientation toward God. As a result, Jesus’ saying in Matthew 16:25–26 cannot coherently be reduced to martyrdom or post-mortem survival.

His key contribution is exegetical clarity: translating psychē as “life” subtly evacuates the verse of its claim on identity.

- Key work

Body, Soul, and Human Life

Green diagnoses the linguistic flattening—but largely leaves unexplored the historical reasons Christians became motivated to flatten it.

B. Michel Foucault — From Self-Loss to Self-Management

Michel Foucault never exegetes Scripture, yet he explains with unnerving precision why a command like “lose your soul” became intolerable.

In his analysis of ancient ethics and early Christianity, practices of self-renunciation—what the Greeks called askēsis—were originally aimed at undoing the self. Over time, these practices were transformed into systems of discipline, confession, obedience, and surveillance.

Once Christianity became institutionally useful, the soul could no longer be something that might be lost. It had to be preserved, monitored, corrected, and governed.

A soul that can be lost is a soul that resists administration.

Foucault supplies the missing middle: how the Church’s concern shifted from transformation to management, making Jesus’ language increasingly dangerous.

- Key works

The Care of the Self

Subjectivity and Truth

C. Charles Taylor — Why Modern Ears Cannot Hear It

Charles Taylor explains why, even when the text is translated accurately, modern readers often cannot hear it.

Taylor traces the emergence of the buffered self—a modern form of identity that is autonomous, sealed, and protected from ontological threat. Within this moral psychology, a command like “lose your soul” sounds not redemptive but pathological. It appears to violate personal integrity and psychological safety.

By contrast, “lose your life” can be reinterpreted as heroic sacrifice.

This explains why modern Bible translation quietly follows plausibility conditions rather than lexical ones.

- Key works

Sources of the Self

A Secular Age

Taylor does not focus on ψυχή, but he shows why translators and preachers increasingly felt they could not mean it.

D. Rowan Williams — Retrieval Without Sentimentality

Rowan Williams is the theologian who most clearly understands what was lost—and what a faithful recovery might look like.

Drawing deeply on the Church Fathers and the contemplative tradition, Williams insists that Christian discipleship entails exposure, loss, and re-formation of desire. The self Christ addresses is not meant to remain intact.

Yet Williams is careful: “lose your soul” does not license coercion, violence, or spiritual abuse. It names participation in kenosis—the self-emptying of Christ (cf. Philippians 2:7)—in which the self is not annihilated but given back, transfigured.

- Key works

The Wound of Knowledge

Being Christian

Williams does not foreground translation history, but he understands the spiritual cost of its disappearance.

E. Why These Four Together

Together, these thinkers form a minimal but complete circuit:

- Green shows what Jesus meant by ψυχή.

- Foucault explains how the Church learned to fear self-loss.

- Taylor explains why modernity cannot hear it.

- Williams shows how it might be recovered without regression.

No single figure tells the whole story.

Together, they explain how Christianity learned to keep Christ—while quietly losing his soul.

Appendix II: The Historical Tragedy

How a saying about salvation as self-loss became a slogan about survival—and why translation followed interpretation.

A. Act I — Jesus and the Dangerous Saying (1st Century)

Jesus’ words in Matthew 16:25–26 hinge on ψυχή (psychē)—a term that, within Second Temple Judaism, names the whole living self: desire, will, identity, orientation before God.

To “lose the soul” is not to flirt with death but to surrender the self one is trying to secure. The paradox targets the egoic project of self-preservation. It is existential, not episodic; daily, not heroic.

Early readers—Greek-speaking and Hebraic—heard this clearly.

B. Act II — Preservation without Translation (4th–10th Centuries)

With the Constantinian shift, Christianity moves from persecuted movement to imperial religion. The saying remains intact in Greek and in Jerome’s Vulgate (anima, not vita), but its use subtly changes.

Salvation begins to mean:

- orthodoxy over transformation

- order over risk

- stability over unmaking

The word survives.

The practice thins.

“Lose your soul” becomes spiritually admirable—but increasingly impractical.

C. Act III — The Soul Becomes an Object (11th–13th Centuries)

With Scholasticism—especially Thomas Aquinas—the soul is carefully defined as the form of the body. Philosophically rigorous, existentially distancing.

The soul is now something one has rather than something one is.

As salvation becomes juridical (see atonement theory), “losing the soul” sounds like failure, not fulfillment. The verse is reinterpreted as:

- hyperbole

- metaphor

- martyrdom rhetoric

Still, the text itself remains unchanged.

D. Act IV — Reformation Anxiety and Interior Suspicion (16th Century)

The Reformation inherits a Church that has weaponized interiority (purgatory, indulgences, penitential economies). Reformers react by distrusting “soul-language” altogether.

Figures like William Tyndale, translating directly from Greek, begin alternating between “soul” and “life”—not from ignorance, but from fear of abuse.

The saying is increasingly framed as:

- willingness to die for Christ

- fidelity under persecution

True, but narrower than Jesus intended.

This is the first moment where interpretation pressures translation.

E. Act V — The Buffered Self and the Final Translation (18th–20th Centuries)

Modernity produces what Charles Taylor calls the buffered self:

- autonomous

- sealed

- psychologically protected

Within this framework, “lose your soul” sounds:

- violent

- pathological

- spiritually abusive

Translators choose “life” not because it is more accurate, but because it is hearable. Modern versions (RSV, NRSV, NIV, ESV) normalize the shift—often with a footnote quietly admitting the Greek says psychē.

The word finally changes because the meaning can no longer be borne.

F. The Structural Pattern

Across two millennia, the same substitution repeats:

- Transformation → Preservation

- Self-surrender → Self-management

- Salvation as death-and-rebirth → Salvation as safety

Once Christianity becomes a system for producing stable selves, a saying about losing the self must be softened—or removed by translation.

G. Why This Is a Tragedy

This is not a story of bad faith or simple error.

It is a story of fear:

- fear of abuse

- fear of instability

- fear of selves that cannot be governed

But Jesus’ saying was never safe.

As John 12:24 puts it:

“Unless a grain of wheat falls into the earth and dies…”

The tragedy is not that the Church misunderstood the Greek.

The tragedy is that it slowly stopped practicing the truth the Greek named.

And when practice vanished,

translation followed.

H. In One Sentence

Christianity did not accidentally lose Christ’s “soul.”

It learned—carefully, pastorally, rationally—

that it could no longer afford to mean it.

Appendix III: Losing Your Psychē

What Jesus meant, what we fear, and what it actually costs to obey.

A. The Word We Keep Translating Away

Jesus’ saying in Matthew 16:25–26 turns on a single word:

ψυχή (psychē).

In modern English, “psyche” suggests:

- mental health

- personality

- interior feelings

But in the first-century Jewish–Greek world, psychē names something far more comprehensive:

- the living self

- the center of desire and will

- the self as oriented toward God or the world

As Genesis 2:7 puts it, humans do not have souls; they are living souls.

To “lose the psychē” is to lose the self as currently configured.

B. What “Losing” Does Not Mean

Jesus is not advocating:

- self-hatred

- psychological collapse

- annihilation of personhood

- repression of desire

Nor is he endorsing a Platonic body–soul dualism where the “real you” escapes the body.

Those are later misunderstandings—often projected backward to make the saying safer.

C. What “Losing” Actually Targets

“Whoever seeks to save his psychē will lose it.”

The target is not existence, but self-preservation.

More precisely:

- the self organized around control

- the self secured by status

- the self justified by success

- the self defined over against others

In contemporary terms, it is the egoic self-project.

Jesus is naming a paradox:

- the self you try to secure cannot survive

- the self you release can be given back

D. Why This Feels Violent to Us

Within modern moral psychology—especially the buffered self described by Charles Taylor—the self is assumed to be:

- inviolable

- sovereign

- entitled to continuity

Any command that threatens dissolution sounds abusive.

But this assumption is historically contingent.

Earlier Christian spirituality assumed the opposite:

- the self is unfinished

- disordered desire must be undone

- salvation involves exposure and risk

Hence the prominence of:

Modern readers hear pathology where earlier Christians heard promise.

E. The Cost Jesus Is Naming

“Lose your psychē” is not a metaphorical flourish.

It names a real cost:

- loss of self-justification

- loss of narrative control

- loss of identity built on comparison

- loss of the right to define oneself apart from God

This is why the saying is paired with:

- “deny yourself” (Mark 8:34)

- “not my will, but yours” (Luke 22:42)

- the grain of wheat that must die (John 12:24)

This is not improvement.

It is death-and-receiving-life.

F. Why Translation Changed When Practice Disappeared

As Christian practice shifted from:

- transformation → moral regulation

- self-loss → self-management

the command became unlivable.

Once discipleship no longer involved the actual undoing of identity, the verse had to be reframed:

- “life” instead of “soul”

- heroism instead of surrender

- future reward instead of present unmaking

Translation followed practice.

G. What It Would Mean to Mean It Again

To recover “lose your psychē” today would not mean:

- romanticizing suffering

- dismantling psychological care

- coercing vulnerability

It would mean recovering a vision of salvation in which:

- the self is not the final authority

- desire can be re-educated

- identity is received, not secured

As Paul puts it:

“It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me”

— Galatians 2:20

That sentence only makes sense if something called “me” has already been lost.

H. In One Sentence

To lose your psychē is not to disappear.

It is to let the self you are desperately trying to save

become unnecessary.

And that—precisely that—is what modern Christianity learned it could no longer risk asking for.

Continued in Lost Self Café v2: Telogos (Christ as Telos)

Leave a comment