Written in the voice of Gustave Thibon, about using suffering to understand goodness rather than vice versa.

A Necessary Clarification

I must begin by saying what Simone Weil herself would have insisted upon:

she did not construct a theodicy at all.

She distrusted systems, explanations, and especially reconciliations.

What follows is therefore not her doctrine, but a gesture of reading—an attempt to name the direction of her attention.

If there is a “reverse theodicy” in her thought, it is one that refuses to justify God, and instead allows goodness to be tested by suffering.

The Usual Error of Theodicy

Philosophy—and theology even more so—habitually proceeds in this order:

- First: God is good

- Then: suffering must be explained so as not to contradict this goodness

Suffering becomes a problem to solve, a datum to be absorbed into meaning.

But this order already presumes what it claims to demonstrate.

Simone Weil rejected this maneuver instinctively.

For her, any goodness that survives only by explaining suffering is already suspect.

Beginning Where Reality Begins

Weil begins elsewhere: with affliction (malheur).

Not suffering in the general sense, but a condition in which:

- the soul is stripped of illusion,

- the intelligence is wounded,

- and meaning itself collapses.

Here, nothing guarantees goodness.

No doctrine protects it.

No metaphysical harmony shelters it.

If goodness exists at all, it must appear here—or not at all.

Why Suffering Explains Nothing

Weil never believed that suffering produces goodness.

Suffering:

- does not purify by itself,

- does not instruct by itself,

- does not redeem by itself.

Left alone, it brutalizes, degrades, and silences.

This is crucial.

To use suffering as an explanatory principle is already to falsify it.

Attention: The Only Passage

What changes everything is attention.

By attention, Weil meant not reflection, not interpretation, but a consenting presence—a suspension of the will that allows reality to be fully real.

By attention, Weil meant not reflection, not interpretation, but a consenting presence—a suspension of the will that allows reality to be fully real.

Attention does not explain suffering.

It dwells with it.

Only here does something like goodness become perceptible—not as an idea, but as a quality of presence.

Incarnation Rather Than Explanation

This is why Weil’s thought is unintelligible apart from the logic of incarnation.

The Word does not justify the world.

The Word enters it.

“[And the Word became flesh and lived among us…]”

— John 1:14

Meaning is not asserted over suffering; it is borne within it.

Meaning is not asserted over suffering; it is borne within it.

Even Christ does not name the goodness of God from the Cross.

He utters abandonment:

“[My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?]”

— Psalm 22:1

That cry is not an answer.

It is attention taken to its limit.

Goodness as What Survives Without Being Claimed

Thus the reversal:

- We do not begin with goodness and make suffering intelligible.

- We begin with suffering and ask whether goodness can still be encountered without being asserted.

If goodness appears, it does so:

- silently,

- without justification,

- without cancelling the suffering that preceded it.

Such goodness cannot be defended.

It can only be recognized.

Why Weil Refused to “Say” This Herself

I am keenly aware that Simone Weil herself would not have written these lines.

She mistrusted formulations that congeal experience into doctrine.

She preferred fragments, not because she lacked rigor, but because truth—at least here—does not totalize.

If I speak of a “reverse theodicy,” it is only to name the direction of her fidelity:

from affliction toward goodness,

never from goodness toward explanation.

Final Word

If there is a lesson to be drawn, it is a severe one:

Goodness is not what explains suffering.

Goodness is what sometimes appears when suffering is attended to without lying.

Anything more would betray Simone Weil.

Appendix: Weil v. Nietzscheon the Death of God

Write as an imagined exchange between Friedrich Nietzsche and Simone Weil

ChatGPT Prompt

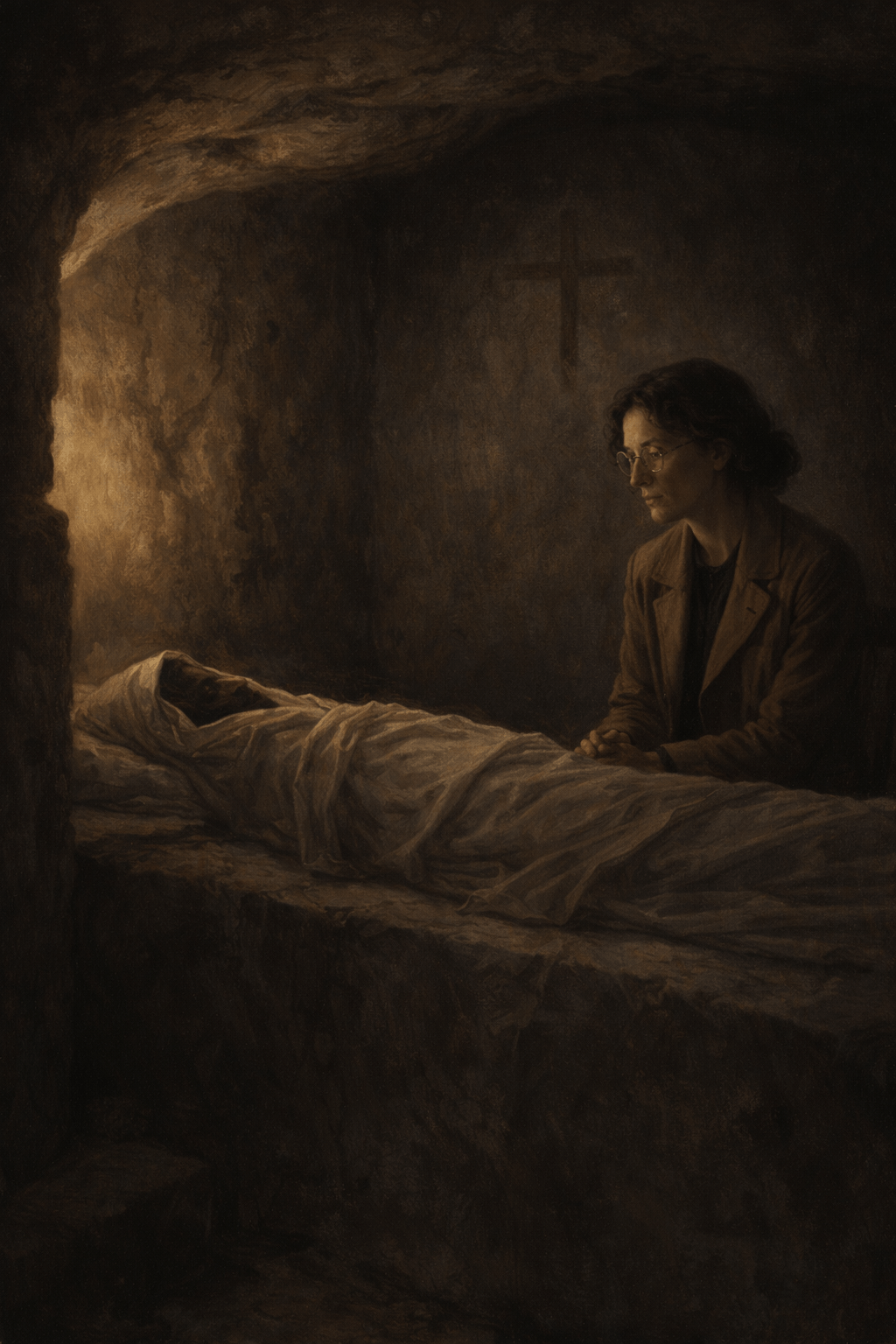

The Meeting

They do not meet in a place of light.

There is no marketplace, no crowd, no proclamation.

They sit instead in a bare room—stone walls, no symbols—where nothing presses them to agree.

Nietzsche speaks first, not triumphantly, but with exhaustion.

Nietzsche

God is dead.

(The phrase echoes The Gay Science §125.)

I did not kill Him alone.

We all did—by our honesty, our science, our refusal of lies.The heavens are empty.

What you call meaning no longer holds.And now the question is whether humanity will collapse under this weight

or become strong enough to create value without illusions.

He pauses.

To deny this is cowardice.

To mourn forever is decadence.

Something must replace Him.

Weil

She does not answer immediately.

When she does, it is not with a counterclaim.

I do not deny the emptiness you describe.

I only ask whether you are too quick to fill it.

She looks not at Nietzsche, but at the space between them.

The God you say is dead—

the God of explanations, guarantees, and rewards—

deserved to die.

Nietzsche

Then you agree with me.

Weil

No.

I agree with what you see.

Not with what you conclude.

She continues quietly:

You look at the absence of God and call it death.

I look at the same absence and call it withdrawal.

Nietzsche

Withdrawal is only a prettier word for nothingness.

If God does not act, does not speak, does not ground value—

what difference remains between absence and nonexistence?

Weil

The difference between force and love.

She turns toward him now.

What withdraws in order not to coerce

is not the same as what never was.

(This follows her account of décréation.)

Nietzsche

Love without power is weakness.

A God who cannot command is no God at all.

Weil

Or He is God precisely because He does not command.

She lets the sentence rest.

Power forces assent.

Truth does not.

Nietzsche

You would have us wait forever—

in suffering, in silence, in negation.That is not life.

That is paralysis.

Weil

No.

It is attention.

She speaks more firmly now.

You fear that without God we must create meaning.

I fear that in creating meaning we will never again encounter God.

Nietzsche

Then what remains?

If we do not create values, and God does not give them,

what is left?

Weil

Fidelity without reward.

Attention without outcome.

Love without justification.

She adds:

If God is present, He is present only here—

where nothing obliges belief

and nothing promises compensation.

Nietzsche

He laughs softly.

You call this God.

I call this emptiness endured by the weak.

Weil

Perhaps.

But I call weak the soul that cannot endure emptiness

without replacing it.

But I call weak the soul that cannot endure emptiness

ChatGPT as Simone Weil

without replacing it.

Silence

They say nothing for a long time.

There is no synthesis.

Nietzsche stands eventually.

If your God exists,

He asks too much.

Weil answers without looking up:

He asks only that we do not lie.

Closing Note

They part without agreement.

Nietzsche walks toward value creation.

Weil remains with attention.

Both refuse consolation.

Only one refuses replacement.

The question of whether God is dead

remains unanswered—

but no longer abstract.

It now bears weight.

Leave a comment