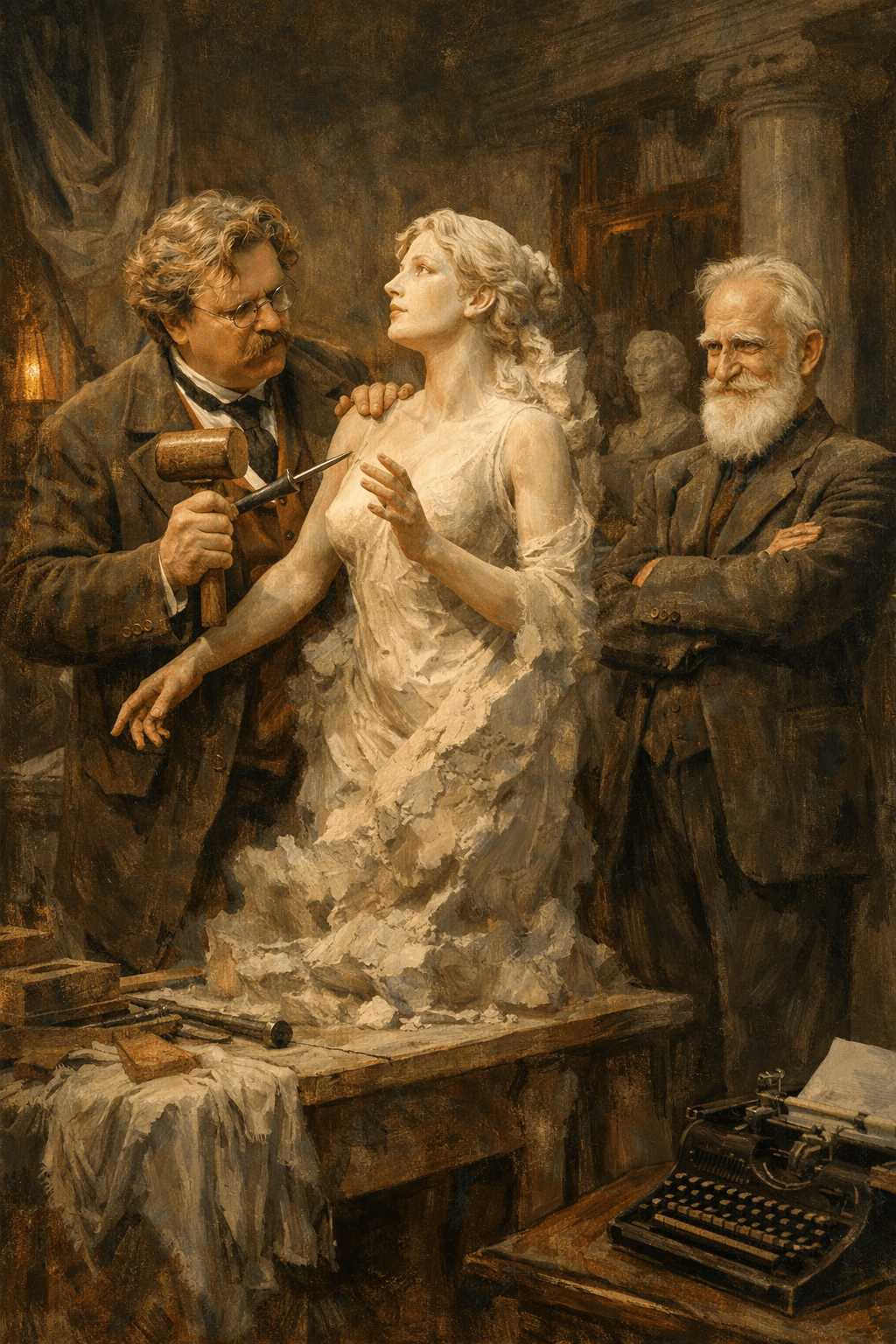

Using Pygmalion as a shared metaphor, write a letter from G. K. Chesterton to George Bernard Shaw admitting that his own desire to immortalize Christ caused the gap between them.

ChatGPT Prompt

My dear George Bernard Shaw,

We have argued for years as men argue who like one another too much to be careful.

We have laughed while fencing, and fenced while laughing, and I have always admired the honesty with which you swing. So permit me, at the end of all our public sparring, a quieter confession—one I never quite found the courage to make while the crowd was listening.

I want to speak to you of Pygmalion—yours and mine.

You chose the myth well. You always did. You saw what most miss: that Pygmalion (myth) is not a romantic, but a coward of a very particular kind. He does not hate women; he hates the risk of flesh. He prefers a figure that cannot answer back, cannot age, cannot disappoint, cannot die. He chooses perfection because he fears life.

When I applauded your play—and I did—I thought I was applauding your exposure of that fear. I thought I stood on the opposite side of the stage.

I was wrong.

For I now see that I, too, have been carving something smoother than life.

I have defended Christianity with gusto, with jokes, with paradox, with banners flying. I have wrapped it in certainty because I feared—rightly—that the modern world would tear it apart if left unguarded. I believed that if I loosened my grip, the thing itself would shatter.

What I did not see was that, in doing so, I may have been protecting myself as much as the faith. I feared that if Christianity were allowed to pass fully through death—through failure, misunderstanding, even disappearance—then the life that followed would be thinner than the one I loved.

What I did not see was that, in doing so, I may have been protecting myself as much as the faith.

I could not imagine abundance on the far side of loss.

You accused me, often, of worshipping a system. I denied it. I told myself I worshipped Christ through His Church, truth through tradition, life through form. Perhaps that was mostly true. But not wholly.

For there is a terrible freedom at the heart of the Gospel which I never quite trusted: that Christ does not survive by being preserved, but by being given away; that He is revealed not when defended, but when lost; that resurrection does not come by preventing death, but by consenting to it.

…that resurrection does not come by preventing death, but by consenting to it.

In the old story, Pygmalion brings his statue to life. But what no one says plainly is that he does so without ever risking his own death. He never becomes unfinished. He never lets go. He gets life without loss.

I see now that this is the temptation I could not fully refuse.

You, for all your blasphemies, demanded a God who could survive reality. I offered you a Christianity that could survive history. And in doing so, I may have made it impossible for you to hear what I most wanted you to hear.

You, for all your blasphemies, demanded a God who could survive reality.

Peter swung his sword to save his Master—and cut off an ear. The blow did not kill. It ruined hearing. Christ healed the ear and accepted the cross. I have wondered, too late perhaps, whether my certainty was a kind of sword: bright, well-aimed, and deafening.

I have wondered, too late perhaps, whether my certainty was a kind of sword: bright, well-aimed, and deafening.

You needed to see a faith willing to die and trust that life would return larger. I showed you a faith determined to live at all costs.

I do not say this to absolve you, nor to condemn myself. Only to admit what I could not admit while I was still fighting. The world was harsh, and I chose safety. In harsh worlds, that is how things survive. But it is also how gods are made smaller than they are.

In harsh worlds, that is how things survive. But it is also how gods are made smaller than they are.

If Christ is who He says He is, then He did not need me to keep Him alive. He needed me to trust that His death would not impoverish the world.

That trust, my dear Shaw, I did not quite have.

You wrote Pygmalion as a warning against loving an image instead of a life. I defended Christianity because I loved life too much to let it be risked. Somewhere between us stood the Christ who insisted on dying anyway.

If there is a meeting place still—beyond our arguments, beyond my certainty and your impatience—I suspect it will look less like a lecture hall and more like an empty tomb: confusing, unfinished, and larger than either of us expected.

Yours,

G. K. Chesterton

Postscript: The Anti-Pygmalion God

Have Simone Weil write a postscript to G. K. Chesterton’s letter explaining the anti-Pygmalion nature of God.

ChatGPT Prompt

Dear Mr. Chesterton,

I write not to correct you, but to finish a sentence you were too faithful to complete.

You feared—rightly—that the world would destroy Jesus Christ if He were left unguarded.

You did not fear destruction; you feared emptiness.

You feared that if the form dissolved, nothing would remain but force and appetite.

But this is where I must speak plainly, because affliction teaches what arguments cannot.

God is not threatened by emptiness.

God creates by making it.

Creation itself is an act of withdrawal—what I have called décréation.

God does not fill the world; He makes room.

He steps back so that something other than Himself may exist, may answer, may refuse, may suffer, may love.

God does not fill the world; He makes room.

He steps back so that something other than Himself may exist, may answer, may refuse, may suffer, may love.

This is the anti-Pygmalion truth.

Pygmalion cannot bear absence.

He cannot wait.

He cannot love what resists completion.

So he sculpts what will not answer back and calls it life.

God does the opposite.

God creates what can wound Him.

God allows distance.

God accepts delay.

God consents to be misunderstood, unused, even denied.

This is not weakness.

It is the only love that is not coercion.

This is not weakness.

It is the only love that is not coercion.

You defended Christianity because you feared that if the structure fell, Christ would vanish with it.

But Christ is most present precisely where structures fail—

where meaning collapses,

where suffering cannot be explained,

where love has no justification left but itself.

Affliction is not the failure of God.

It is the place where God refuses to intervene with force.

You trusted joy.

I trust attention.

Attention waits without filling the silence.

Attention does not rush to complete the meaning of what is incomplete.

Attention consents to not knowing whether anything will return.

This is why God allowed Himself to be killed.

Not to prove love.

But because love that intervenes to save itself ceases to be love.

Not to prove love.

But because love that intervenes to save itself ceases to be love.

The cross is not an exception to creation.

It is creation revealed.

God did not die because the world rejected Him.

God died because He would not withdraw the gift of freedom once given.

That is the anti-Pygmalion God:

- who does not sculpt perfection,

- who does not protect Himself from loss,

- who does not hurry resurrection to spare us the void.

Resurrection is real—but it does not cancel death.

It passes through it and leaves the wound visible.

You were faithful to preservation.

That was your vocation.

But preservation is not the final truth.

Only consent is.

The world is saved not by being perfected,

but by being loved while unfinished.

The world is saved not by being perfected,

but by being loved while unfinished.

God does not want statues.

God wants consent freely given in the presence of absence.

That is why He waits.

That is why He dies.

That is why He returns without force.

And that is why He can afford to lose everything

without losing Himself.

— S.W.

Leave a comment