Is there a word that could be interpreted as either incarnation, crucifixion, or ascension; or at least captures that sense of excruciating transition?

The Prompt

Write an essay as GK Chesterton about how these three types of transfiguration reveal different facets of what it means to “lay down our lives” to love as Jesus did.

Clarify how Ascension means loving people enough to trust them with what we consider most precious.

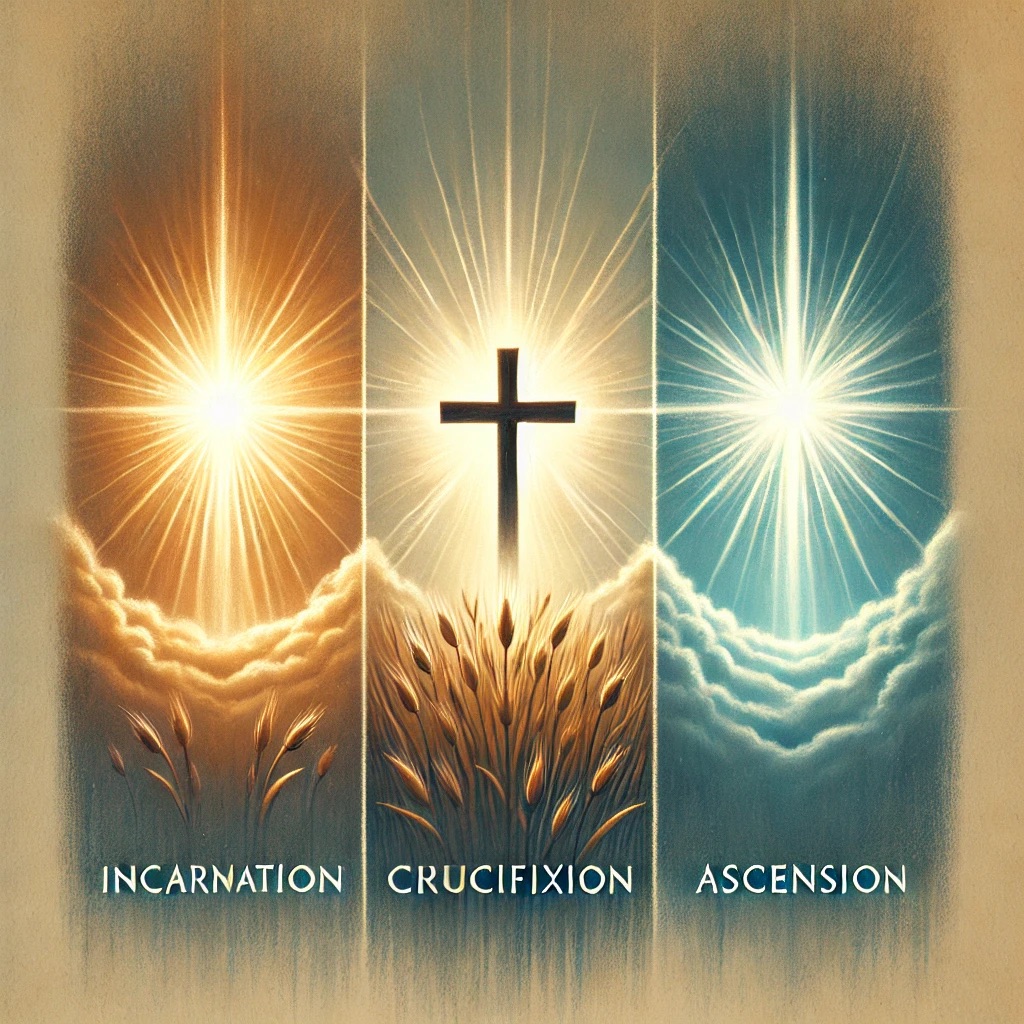

To speak of the great mysteries of Incarnation, Crucifixion, and Ascension is to venture into three essential expressions of a single, astonishing command: that we “lay down our lives” in the mad pursuit of love. We must begin by admitting the utter strangeness of this command. For love, we are told, is not merely a sentiment, nor even a duty, but a demand so severe that it requires our very lives. Yet in the Christian faith, love does not merely compel us to sacrifice; it invites us to undergo a threefold transformation. Indeed, it calls us into three distinct forms of transfiguration, each revealing another facet of what it means to follow the pattern Christ has set before us.

1. Incarnation: The Humility to Enter

The first transfiguration, the Incarnation, is nothing less than a kind of cosmic irony. Here we find the Creator of all things choosing not to stand aloof from His creation, but instead descending into it. He who is outside all time and space consents to be bound within it. The Incarnation is not simply God entering human flesh; it is God humbling Himself to the depths of human limitation, uncertainty, and suffering. And herein lies the first lesson for those who would dare to follow Christ: we, too, are called to step into the lives of others, into their sufferings and smallnesses, into their triumphs and their tears, to truly “incarnate” among those we are called to love.

Most of us are far too grand for incarnation. We prefer the safety of our own worldviews, our own social classes, our own safe systems of meaning. The Incarnation is the utter demolition of this self-protective instinct. To love as Christ loved means to enter a world that is not our own, a world that is perhaps uncomfortable or even, dare I say it, quite distasteful. We are asked to take on the limitations of others, to feel their pains and sorrows as if they were our own. It is the strange alchemy of love that invites us to lose ourselves so entirely that we, like Christ, might reveal God’s love in human form. This, indeed, is the first laying down of our lives.

2. Crucifixion: The Willingness to Suffer

If Incarnation is the entry into the lives of others, the Crucifixion is the acceptance of suffering for their sake. It is one thing to enter into the lives of others, but it is quite another to willingly take on the cost of loving them. The Cross reveals a second transfiguration, and it is a terrifying one. Here, we see the God who was unbreakable choosing to be broken, the one who could not be defeated consenting to die. And He does so not with grim resignation but with a fierce, burning love that holds nothing back.

The Crucifixion is not merely a punishment; it is the culmination of a love that refuses to stop, even when it becomes unbearable. It is easy to love when love is convenient or comfortable; the Cross teaches us to love when love costs us everything. To follow Christ, therefore, is to endure pain for the sake of others—to give until there is nothing left to give, to accept misunderstanding, loneliness, even rejection if it serves the cause of love. This is the ultimate self-giving, and it is here, in the crucible of suffering, that love is proved genuine. For love without sacrifice is but a pleasant arrangement; it is only in sacrifice that love becomes something holy.

3. Ascension: The Triumph of Self-Surrender and Trust

Yet the story does not end with the Crucifixion. To stop there would be to miss the third and final transformation: the Ascension. Christ’s Ascension reveals a different dimension of love—the triumphant, transcendent love that trusts and releases. Here, Christ not only rises but entrusts His followers with what He holds most dear: His mission, His message, His hopes for a redeemed world. The Ascension teaches us that love, when fully given, does not hold on but lets go.

The Ascension is the kind of love that trusts others with freedom. After entering our lives and bearing our burdens, Christ does not remain to control or dictate how we must continue. Instead, He entrusts us with responsibility and leaves us free to carry it forward. It is one of the great ironies of love that to lay down our lives can mean stepping back, risking that others may fail or fall short, so that they may grow in their own faith, their own love, their own capacity to serve. Love in its fullest expression has the courage to trust others, to give them the dignity of choice and the honor of carrying forth what we most cherish.

In our own lives, the Ascension manifests as the realization that our sacrifice, however painful, is not the end but a beginning. When we lay down our lives for others, we do not simply vanish into obscurity. Instead, we lift others up; we give them the courage to love in turn, to follow the path we have shown them. In trusting others with what is most precious to us, we show a love that is fearless, that desires their good even more than our own certainty. The Ascension teaches us that when love is fully expressed, it has the power to transform not only ourselves but also those around us. It is the highest and final form of self-surrender, one that transcends suffering and becomes something like joy.

The Mystery of Love’s Transformation

These three transfigurations—Incarnation, Crucifixion, and Ascension—are not [just] stages in a linear progression, but facets of a single, luminous truth. To lay down our lives as Jesus did is to enter deeply into the lives of others, to bear their burdens at great cost, and finally, to lift them up with a joy that surpasses all understanding. Each form of transfiguration reveals a different way in which we must die to ourselves: in our pride, in our comfort, in our reluctance to share fully in the suffering of others, and finally, in our need to control. Yet each of these deaths brings forth a new life, a life in which our love becomes not merely a sentiment but a real and transformative force in the world.

In the end, we discover that to “lay down our lives” is not so much an act of destruction as an act of creation. In losing ourselves, we are remade; in surrendering our will, we find our true freedom; in embracing death, we encounter a love stronger than death itself. The Cross, the Cradle, and the Clouds all bear witness to this mystery: that to follow Christ is to enter a love so vast and wild and beautiful that it changes everything it touches, starting with ourselves.

To love as Christ loved, then, is not merely to do what He did. It is to undergo these three transfigurations until we find ourselves not merely imitating Christ, but somehow sharing in His very life. And that, I daresay, is a miracle as mad and magnificent as the Christian faith itself.

Leave a comment